Six Epstein Methods of Working With Families Found in Exemplary Schools

First developed by Joyce Epstein and collaborators in the early 1990s, the Framework of Six Types of Interest—sometimes called the "School-Family unit-Customs Partnership Model"—has undergone revisions in the intervening years, though the foundational elements of the framework take remained consistent. Epstein's Framework of Six Types of Involvement is ane of the virtually influential models in the field of school, family, and community engagement and partnership.

To support ongoing research and practice related to school, family, and community partnerships, Epstein and colleagues founded the Center on School, Family unit, and Community Partnerships and the National Network of Partnership Schools, which are function of the Eye for Social Organization of Schools in the School of Education at Johns Hopkins Academy.

"The style schools intendance about children is reflected in the way schools care about the children's families. If educators view children simply as students, they are probable to see the family as split from the school. That is, the family unit is expected to do its chore and leave the education of children to the schools. If educators view students as children, they are likely to come across both the family unit and the community as partners with the schoolhouse in children'southward didactics and development. Partners recognize their shared interests in and responsibilities for children, and they work together to create better programs and opportunities for students."

Joyce Epstein, "School/Family/Community Partnerships," Phi Delta Kappan

The most recent version of the Framework of Six Types of Involvement is described in School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action (4th Edition, 2019), which is co-authored by Epstein and several collaborators: Mavis Yard. Sanders, Steven B. Sheldon, Beth S. Simon, Karen Clark Salinas, Natalie Rodriguez Jansorn, Frances L. Van Voorhis, Cecelia S. Martin, Brenda Grand. Thomas, Marsha D. Greenfeld, Darcy J. Hutchins, and Kenyatta J. Williams.

In addition to the framework introduced here, the handbook outlines a comprehensive model of school-family unit-customs partnerships that includes several components, including the development of a school-based action team that can lead partnership initiatives, the creation and implementation of an action program outlining partnership strategies and programs, the evaluation of quality and progress, and the continual improvement of school-family-community partnerships from yr to twelvemonth. The authors annotation that the Framework of Six Types of Involvement is intended to support the development and implementation of a systemic approach to partnerships, ideally one that cultivates a "civilization of partnerships" throughout a district or school.

The Framework of Half-dozen Types of Interest builds off Epstein's theory of overlapping spheres of influence. The theory distinguishes an interdependent view of school-family-community influences from what could be considered a separate view of influence. Epstein explains the theory with an example:

"In some schools there are yet educators who say, 'If the family would but do its job, we could do our job.' And in that location are still families who say, 'I raised this kid; at present it is your chore to educate her.' These words embody a view of split up spheres of influence. Other educators say, 'I cannot do my job without the help of my students' families and the back up of this community.' And some parents say, 'I really need to know what is happening in school in gild to assist my kid.' These phrases embody the theory of overlapping spheres of influence."

In other words, the near constructive school-family-community partnerships—i.east., those that accept the greatest positive influence on a student'southward social, emotional, cognitive, and educational development and thriving—recognize that the 3 chief "spheres" of influence practise not operate independently of one another, merely are mutually reinforcing—or mutually undermining. Epstein further explains the theory by describing how authentic school-family-community partnerships (i.e., those that are positively mutually reinforcing) work in practise:

- Family unit-Like Schools: "In a partnership, teachers and administrators create more family-like schools. A family-like school recognizes each child's individuality and makes each kid experience special and included. Family-similar schools welcome all families, not just those that are piece of cake to reach."

- School-Like Families: "In a partnership, parents create more than school-like families. A schoolhouse-like family unit recognizes that each child is besides a student. Families reinforce the importance of school, homework, and activities that build educatee skills and feelings of success."

- School- and Family-Like Communities: "Communities, including groups of parents working together, create school-like opportunities, events, and programs that reinforce, recognize, and advantage students for practiced progress, creativity, contributions, and excellence. Communities also create family-like settings, services, and events to enable families to amend support their children.

The Framework of Half-dozen Types of Involvement is based on decades of inquiry and practice in the fields of educational engagement and school-family-customs partnerships. Summarizing the large body of empirical bear witness supporting the model, Epstein provides the following helpful synopsis of a few patterns identified in the research literature:

- "Partnerships tend to decline beyond the grades, unless schools and teachers work to develop and implement advisable practices of partnership at each grade level."

- "Affluent communities currently have more positive family unit involvement, on average, unless schools and teachers in economically distressed communities piece of work to build positive partnerships with their students' families."

- "Schools in more economically depressed communities brand more contacts with families nearly the problems and difficulties their children are having, unless they work at developing balanced partnership programs that also include contacts almost the positive accomplishments of students."

- "Single parents, parents who are employed exterior the home, parents who live far from the school, and fathers are less involved, on average, at the school building, unless the schoolhouse organizes opportunities for families to volunteer at various times and in various places to support the school and their children."

Every bit the summary above illustrates, anticipated patterns of school, family, and customs disconnection will upshot unless educators, students, families, and community members take affirmative, proactive steps to address negative overlapping influences and build positive, mutually beneficial partnerships. That's where the Framework of Six Types of Involvement comes in.

The Framework of Six Types of Involvement

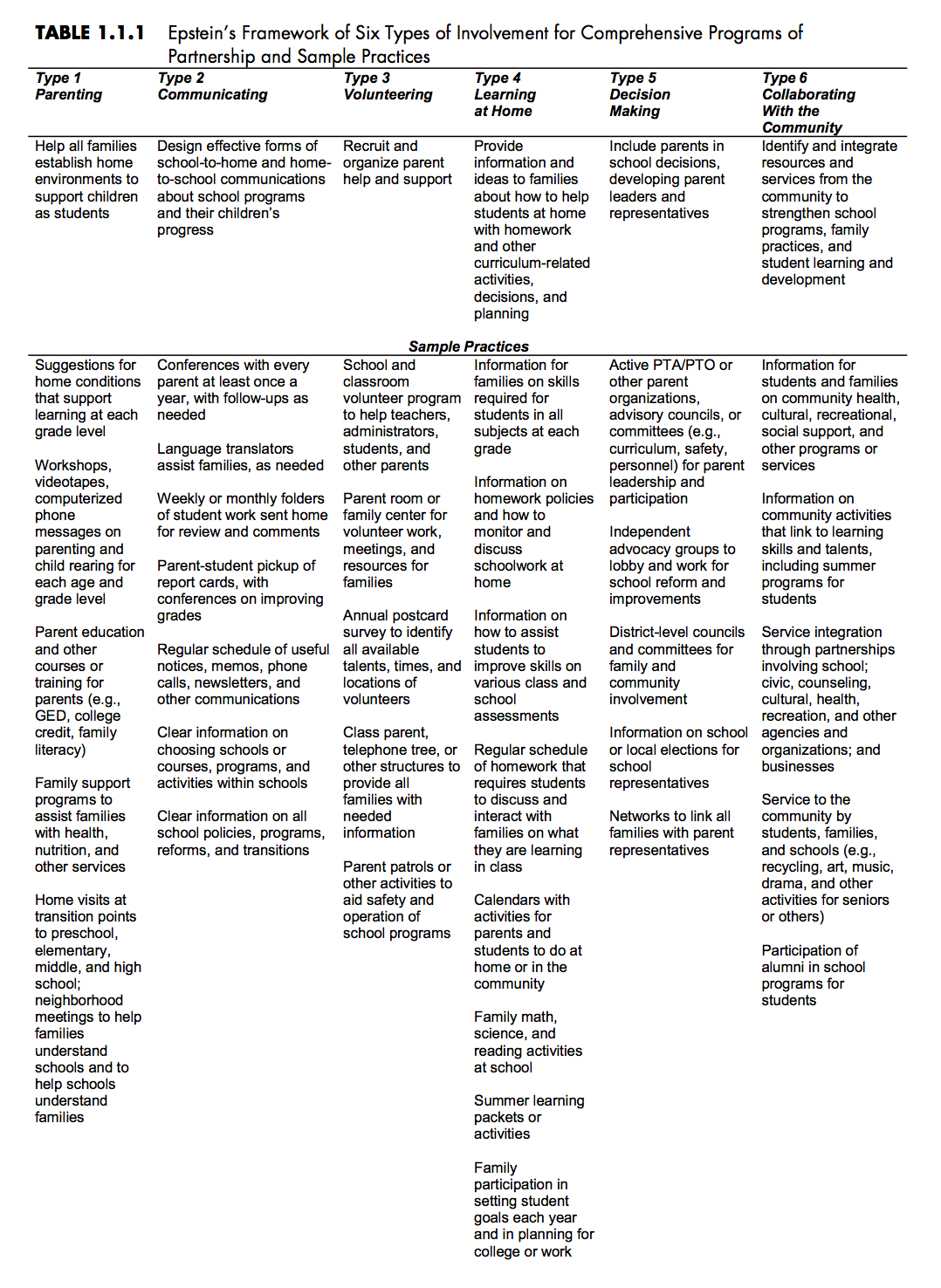

The full technical proper noun of Epstein's framework is the Framework of 6 Types of Involvement for Comprehensive Programs of Partnership and Sample Practices. When discussing the framework, Epstein and her collaborators emphasize that each type of involvement is a two-way partnership—and ideally a partnership that is co-developed by educators and families working together—not a i-way opportunity that has been unilaterally determined past a school.

The six types of involvement are:

- Parenting: Type 1 interest occurs when family practices and home environments back up "children every bit students" and when schools understand their children'due south families.

- Communicating: Type 2 interest occurs when educators, students, and families "design constructive forms of schoolhouse-to-home and home-to-school communications."

- Volunteering: Type iii interest occurs when educators, students, and families "recruit and organize parent assist and back up" and count parents every bit an audition for student activities.

- Learning at Home: Type 4 interest occurs when information, ideas, or training are provided to educate families nearly how they can "aid students at home with homework and other curriculum-related activities, decisions, and planning."

- Decision Making: Type 5 involvement occurs when schools "include parents in school decisions" and "develop parent leaders and representatives."

- Collaborating with the Customs: Type 6 involvement occurs when community services, resources, and partners are integrated into the educational procedure to "strengthen school programs, family practices, and student learning and development."

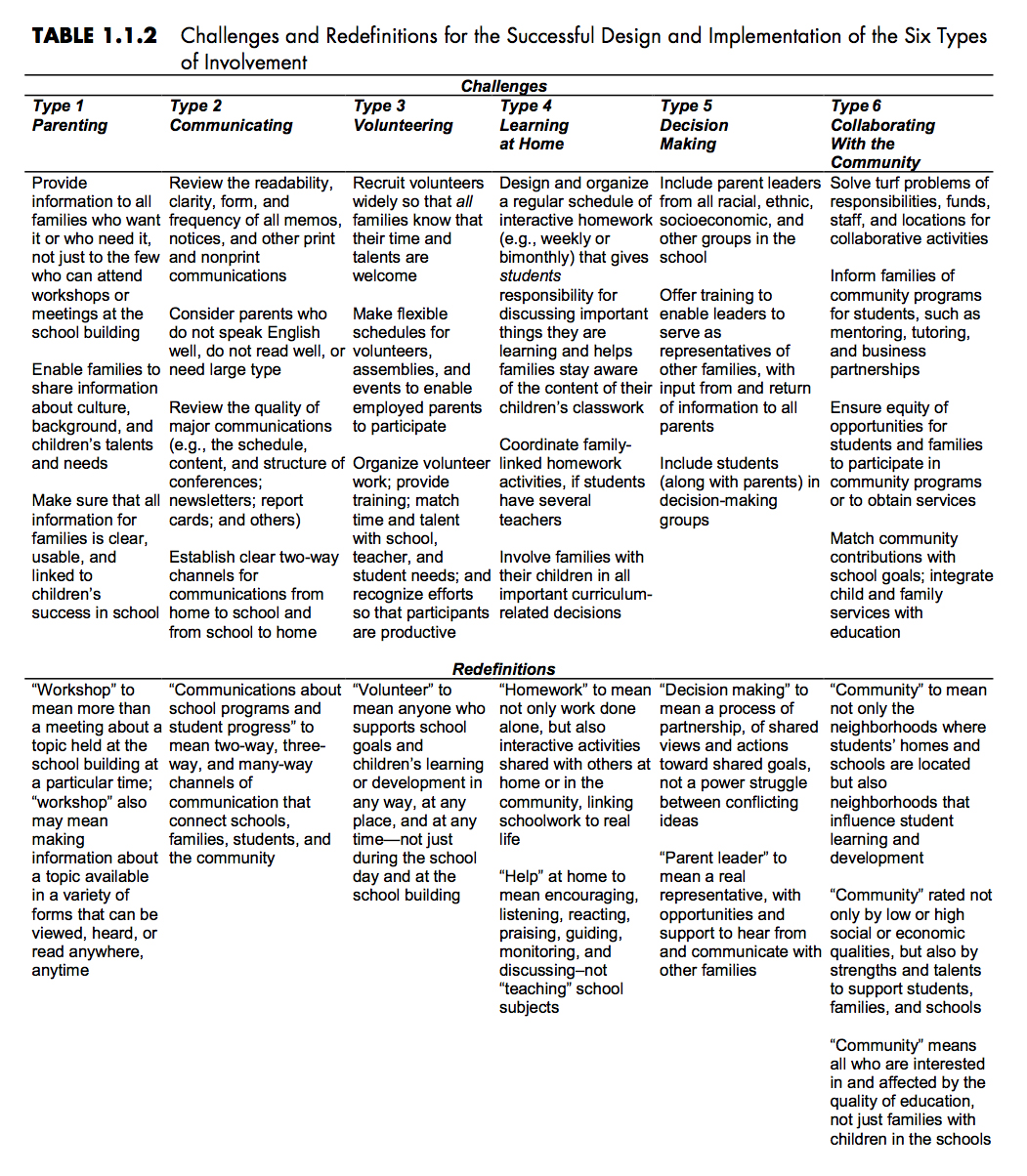

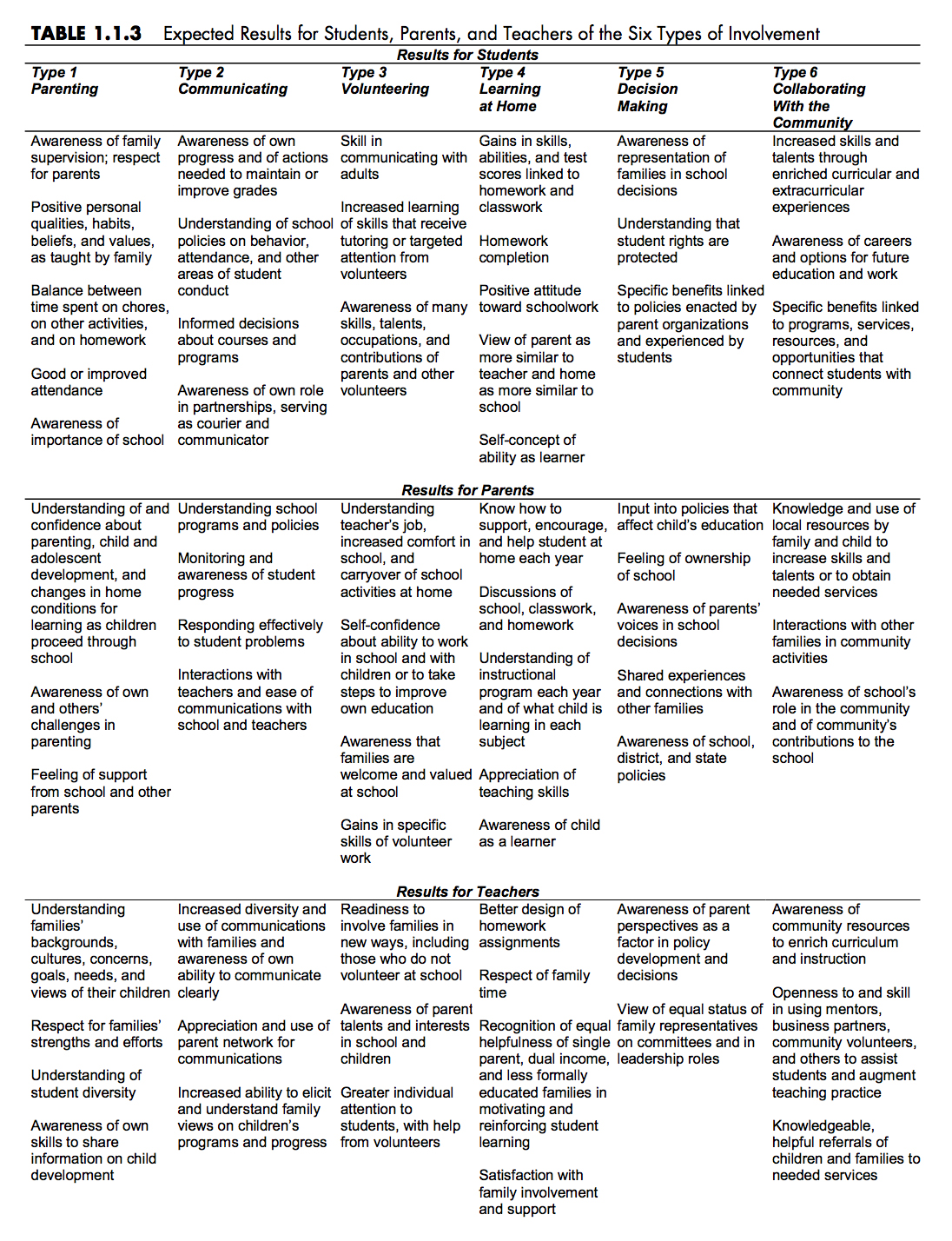

What distinguishes Epstein's framework from many like frameworks is the extensive lists of descriptive examples that Epstein provides to illustrate how each blazon of involvement works in real-life settings. Rather than relying on an abstract metaphorical presentation (such equally a Venn diagram) to explain the model, Epstein and her colleagues developed a set of three comprehensive tables:

1. The beginning table describes the half dozen types of involvement higher up and provides an attendant gear up of representative practices and strategies:

2. The second table—entitled Challenges and Redefinitions for the Successful Design and Implementation of the Six Types of Involvement—presents a set of "challenges" to forms of involvement (i.e., alternative methods and problems that will need to be solved), as well as redefinitions of conventional terms such as workshop, volunteer, or community:

3. The third table—entitled Expected Results for Students, Parents, and Teachers of the Vi Types of Interest—provides descriptions of representative outcomes of the half dozen types of involvement for students, parents, and teachers:

While the Framework of 6 Types of Interest provides a level of detailed description absent from similar models, Epstein addresses a few limitations of the framework. For example, Epstein writes, "The tables cannot bear witness the connections that occur when one practice activates several types of involvement simultaneously." The tables are useful because they provide simplified, well-organized presentations of complex social and organizational dynamics, but similar all simplifying models the tables cannot take into account every gene that may positively or negatively impact unlike forms of involvement and school-family-community partnership, including the myriad cultural dynamics at play in any given school or community.

Epstein too points out that the tables "simplify the circuitous longitudinal influences that produce various results over fourth dimension." Even the best-designed programs can produce poor results for reasons that may be elusive to those involved. And as fourth dimension goes on, and the weather of whatever given programme or approach evolve, the parsing of positive and negative influences and causes may be fifty-fifty more difficult to isolate and identify.

For example, the tables practice not directly address larger questions, such every bit disproportionality in school-family-customs power; the harmful effects of influences such as institutionalized bias, discrimination, and racism; or strategies such as community organizing and protest that aim to wrest some degree of power abroad from institutions that may be reluctant or unwilling to share power or partner in authentic ways with students and families. Ane of the hazards of omitting frank discussions of power, privilege, or prejudice, for case, is that people may offset doing the right things, but they may do them for the wrong reasons, which tin issue in new programs that but reproduce the same issues, conflicts, discrimination, or inequitable results every bit the one-time programs.

Summarizing the options available to schoolhouse, family, and community partners, Epstein provides readers with the following consideration:

"Schools have choices. At that place are two common approaches to involving families in schools and in their children'south instruction. One approach emphasizes disharmonize and views the school as a battleground. The conditions and relationships in this kind of surroundings guarantee power struggles and disharmony. The other approach emphasizes partnership and views the school as a homeland. The conditions and relationships in this kind of environs invite ability-sharing and common respect, and allow energies to be directed toward activities that foster student learning and evolution. Even when conflicts rage, however, peace must be restored sooner or subsequently, and the partners in children's education must work together."

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Joyce Epstein for her contributions to improving this resources and for permission to reproduce images from School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action (Third Edition).

References

Epstein, J. L., et al. (2019). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Printing.

Epstein, J. L. (May 1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children nosotros share. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712.

Artistic Eatables

This work by Organizing Appointment is licensed nether a Creative Eatables Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.

Source: https://organizingengagement.org/models/framework-of-six-types-of-involvement/